How I keep my Git source control history clean

A story about super-developers

I’ve heard stories that there are people that believe that the code is the only documentation they need. I could not believe that is true, until I’ve met such folks in person. For some reason, they are capable of rewriting code without the need to understand what that code was trying to do in the first place. They remove weird constructs because they somehow know why it was needed in the first place. Or they have some special skill that allows them to deduce the purpose of a block of code just by looking at what the code does right now. I don’t have such skills, and don’t believe anybody else has. Maybe they just don’t care. Maybe they only write new code and never have to maintain anything they, or others, have written six months ago. But after 23 years of software development experience, I’ve learned to value the past.

Why I care about that past

To capture that past, I will make sure we capture design choices in Architecture Decision Records and try to deliver my code changes in well-structured commits. I regularly use Github’s excellent blame view and particularly like that little icon in the gutter to go back into history. I also prefer to be able to do a code-review of a pull request (PR) commit by commit and not having to drill through hundreds of unrelated code changes at the same time. You won’t believe how often I see a 100-file PR getting approved without a single comment. In fact, I’ve started to observe a direct correlation between the clarity and structure of a PR and the thoroughness of the review. And isn’t that the entire purpose of peer reviews? And don’t dismiss the fact that a nice focused commit makes cherry picking or porting some related changes between branches much easier.

What I do to protect the past

Well, if you ask me, there’s a couple of things I do myself. First of all, each commit should contain only closely related changes. So anything else, like refactorings, moving of files and renames of code constructs go in separate commits. I even keep unrelated one-liners in separate commits. And if all of this means that I sometimes have to start a new branch, copy those unrelated changes or reapply a refactoring, and then get that merged through a separate PR, so be it.

Each commit also has a title and description that explains what it tries to do and why. So a simple Bumped Json.NET to 10.0 is not enough. I want to know why this was necessary. Quite often there’s something that triggered you to bump that library, so I want to understand why. Even if you only did it to stay up-to-date, I’d like to see that mentioned in the title or description. The same applies to the PR title and description. It either copies the title and description of the most important commit, or, if you decide to squash everything, should contain everything I just mentioned.

I don’t think that’s too much to ask. Some even go further with so-called Atomic Commits, but I’m not yet ready for that level of discipline. Others also say its better to move those unrelated changes into separate PRs. That’s true, but IMO much more work compared to what I’m going to show you below.

Quite often, you’ll hear excuses along the lines of “it’s too complicated” or “I don’t work/think like that”. IMO, that either means somebody lacks the ability to structure their work (which is a problem by itself), or is not using the right tool for the right job. So let’s look at the development workflow I’m using myself.

How I keep my history clean

Depending on the situation, it often starts with the following commands.

git bdone

git cob Fix/SomeBug

This will switch the working directory back to the develop branch, update the local repository with the latest changes from the remote and then create and checkout a new branch called Fix/SomeBug. Both are part of the many shortcuts introduced by the brilliant article Github Flow Like a Pro with these 13 Git Aliases.

Then the real work starts. But whatever happens, at some point in time (and hopefully a couple of times per day), I run:

git save

git push origin -f

This will take whatever changes exist in my working directory, commit those under the title SAVEPOINT and push them to my fork on Github. This is not a big deal by itself, but the fact I don’t have to think about it or even name the commit (like you need with `git stash) is very convenient. After that, I’ll just keep amending any additional changes to that same commit with

git commit --amend

git push origin -f

In order not to obfuscate my upcoming pull request too much, I sometimes deliberately decide to take a step back and reapply some refactorings on a fresh branch. For instance, if I discover that moving a file or fixing a namespace causes a ripple of changes that will explode the size of my PR. Being able to undo those refactorings without loosing the meat of the changes is the main reason why I keep pushing them to my fork regularly. This not always necessary though because quite often, Rider seems to be able to undo a refactoring from inside the IDE.

Regardless, at some point, I’m ready to change that big ball of changes into something that is a bit easier to review and understand. This is when I run:

git undo

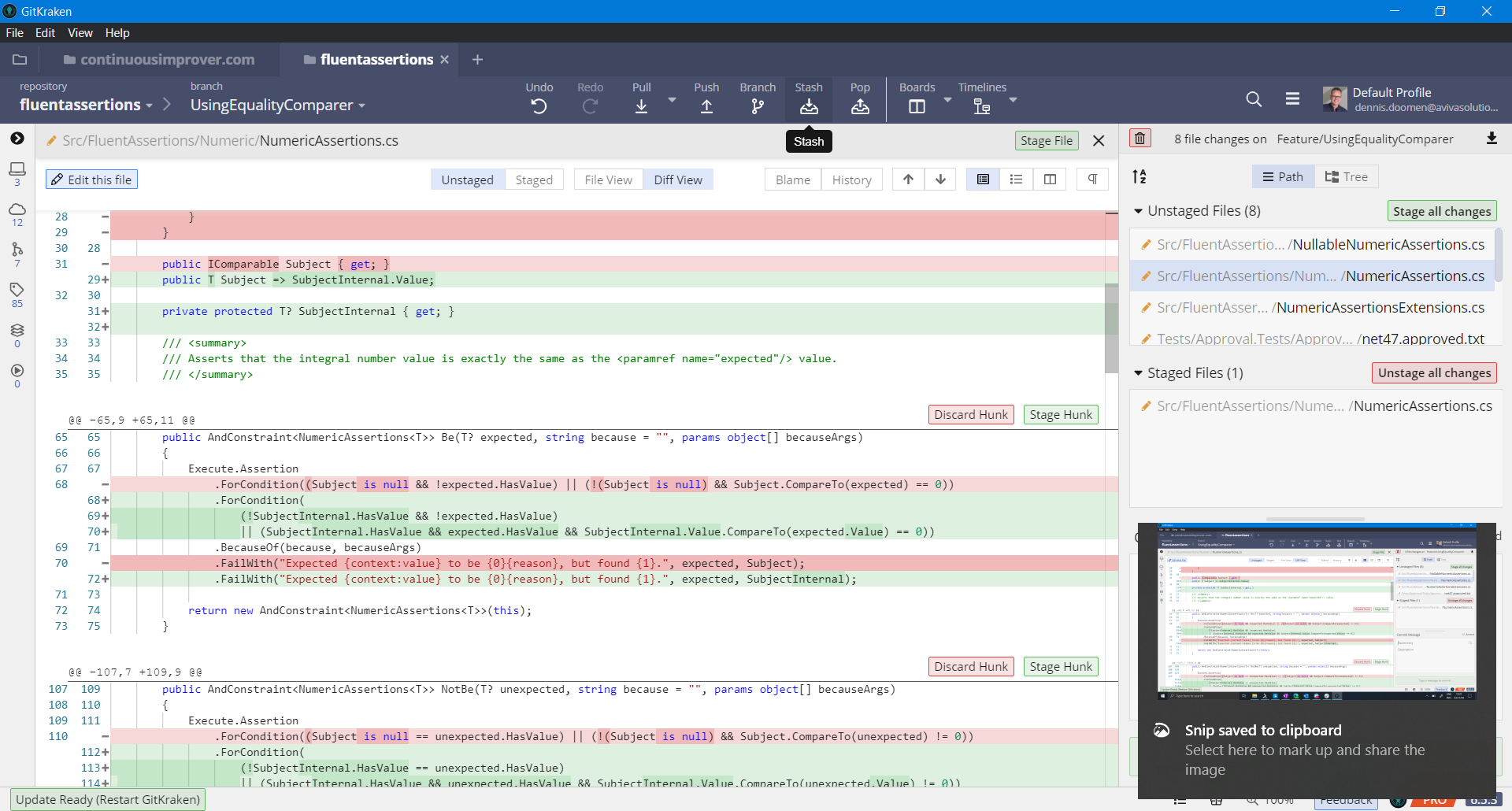

This is nothing but an alias for git reset HEAD~1 --mixed and resets my branch to the commit preceding the aforementioned SAVEPOINT while keeping the changes in the working directory. After that it’s time to launch GitKraken, my preferred GUI for giving me a visual overview of repo and the uncommitted changes.

This is where I decide which files or chunks need to be staged in the same commit. This usually doesn’t take me more than a couple of minutes and is worth the time. Not only will this allow my peer to review the commits one-by-one on Github, it will also keep the source control history clean.

Dealing with code review comments

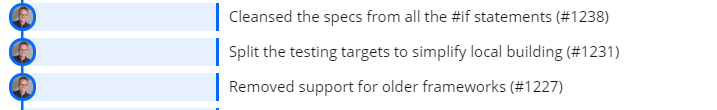

Assuming that my peers do a useful code review, it is inevitable there will be some comments to address. Now what if that effects any but the last commit in my pull request? Will I just commit those changes as a new commit with infamous titles like Code review comments, Fixes or More fixes? No, I won’t. Assuming we were talking about the last commit in the screenshot, this is what I do after staging the chunks of rework through GitKraken or using git add .:

git commit --fixup :/Removed

or

git commit --fixup 0f7a80b46

Either command-line will produce a new commit containing the staged changes with the title fixup! Removed support for older frameworks (#1227). You can repeat this as many times as you want and associate specific chunks of rework with the original commits that contain the changes. Now, to work towards the final result, run the following:

git rebase -i develop --autosquash

git push origin -f

This will start an interactive rebase on develop and reorder the commits in such a way that the fixup commits will be squashed into the original commits. At the end, this will result in the same three commits from the screenshot but with commit hash. And don’t worry that Github will drop the original review comments because of that. Since a year or so, it’s smart enough to associate the review comments with the force-pushed commit.

Since this --autosquash option is something I always use, you can easily make that the default for your machine:

git config --global rebase.autosquash true

Similarly, if you prefer to have shorted versions of the commands used in the example, just define your own aliases like me:

git config --global alias.fixup 'commit --fixup'

git config --global alias.amend 'commit -a --amend -n --no-edit'

git config --global alias.force 'git push origin -f'

Wrapping up

Well, that was a longer post than I planned to. So what do you think? Do you agree that a clean source control history is as important as any other engineering principle? If so, what do you do to keep it clean and organized? And if you didn’t think it was worth the effort, did I manage to change your mind? Let me know by commenting below. Oh, and follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for suggestions and ideas to become a better professional.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment