14 reasons for adopting Nuke as your next build automation tool

What’s the big deal?

I recently had to make some changes on an .NET open-source project I was contributing to and which was using BullsEye, a .NET Core/C# based build automation system. Knowing the author, I guess this project was started because he wasn’t very happy with other attempts like Cake or PSake. It’s a very lightweight library and is often combined with SimpleExec to invoke other command-line tools. The only thing it does is define targets and their dependencies. I prefer libraries over frameworks as well, so I totally see it as a valuable addition to the .NET ecosystem.

However, while trying to modify and understand that C# build script, I started to notice some things that I didn’t quite like. For instance, targets are identified as string values, so you can’t easily navigate from a target to its implementation. But what struck me the most was how bare to the bone the code is. No abstractions, no helper functionality, no built-in support for anything. And that can be a good thing for a while, until you start to feel the need to build your own framework on top of it. I’ve seen a lot of build scripts in my career, and they tend to grow quickly and organically. And in all those cases, those scripts end up being quite long, need lots of (secure) parameters that the build server need to provide, involve complicated command-line invocations, or even need clean-up steps. And then I ignore the fact that such a script will usually also trigger an equally complicated Webpack JavaScript build pipeline. Being able to refactor that C# code with your favorite IDE just like any other code quickly becomes a necessity.

Although I eventually managed to work around most of these issues, I realized that a lot of the challenges that I was facing could be resolved using Nuke, an open-source build framework for .NET that finally fixes some of the design choices in Cake.

Why Nuke?

I’ve had a lot of prior experience with the XML hell of MSBuild, the PowerShell sizzle of PSake and the “feels like C# but doesn’t quite act like it is” Cake approach, both in my open-source projects as well as in professional projects. But nothing has made it such a sweet and smooth experience as Nuke did. The idea of using C# and .NET Core for build scripts that Cake introduced was a great idea, but because it didn’t adopt C#/.NET fully, it became a painful exercise of plain text editing.

I’ve been using Nuke for a while and it solved all of those concerns in a very well designed way. Since the documentation is quite comprehensive, let me share you some of the things I think make Nuke such a blessing.

Getting starting is so trivial

Just being able to run dotnet tool install Nuke.GlobalTool --global and then nuke :setup to run a wizard on an existing repository is simply brilliant.

Auto-downloading .NET Core SDKs

Given the below global.json in the root of the repo:

{

"sdk": {

"version": "3.1.100"

}

}

If the hosting environment (such as a build agent machine), doesn’t have the right version installed, Nuke will automatically download that specific .NET Core SDK into a local folder. And this works both on Windows as well as Linux machines.

The build project is part of your solution

The default nuke :setup will add a new C# project, typically called _build, to your solution. So navigating, debugging or refactoring your build script becomes as trivial as it is in all your other production code. And not only that. Intellisense, code style rules, jumping between targets and adding NuGet dependencies for specific targets just work as expected.

Targets as properties instead of strings

In its simplest form, a target with a dependency can look like this:

Target Build => _ => _

.DependsOn(Clean)

.Executes(() =>

{

DotNetBuild(s => s

.SetProjectFile(Solution)

.SetConfiguration(Configuration.Debug)

.SetAssemblyVersion(GitVersion.AssemblySemVer)

.SetFileVersion(GitVersion.AssemblySemFileVer)

.SetInformationalVersion(GitVersion.InformationalVersion));

});

If you look closer at this syntax, you can see that you’re just defining a property Build of type Target. Because of the usage of variables like _, it’s not entirely evident what’s happening here. But Target is just a delegate that expects an ITargetDefinition and returns a ITargetDefinition. Because of using typed identifiers instead of strings, navigating between dependencies or finding a target is a breeze.

You can run targets without its dependencies or skip individual dependencies

Given the below target definition:

Target Pack => _ => _

.DependsOn(ApiChecks)

.DependsOn(TestFrameworks)

.DependsOn(UnitTests)

.Executes(() =>

{

//

});

Running build.ps1 pack without arguments will ensure all dependencies of the Pack target as well as all of their dependencies are run first. Sometimes you don’t want that (especially while debugging a failing target), and that’s where the --skip parameter comes in. For instance, --skip UnitTests tells Nuke to skip that specific target while building Pack and --skip without anything else will make Nuke skip all the dependencies.

Hide internal targets

If your build scripts are quite big, it may be useful to make it explicit which of the targets are designed to be started directly and which are just supporting the others. This can be achieved with the Unlisted method, like this:

Target SomePrivateStep => _ => _

.Unlisted()

.Executes(() => { });

Targets can define required parameters as well as conditions

Imagine you define a parameter ApiKey that is used used by a target to push a package to NuGet:

[Parameter("The authentication key to use to authenticate to NuGet")]

string ApiKey { get; }

Now let’s use that parameter as a requirement for a target.

Target PushToNuGet => _ => _

.Requires(() => ApiKey != null)

.OnlyWhenStatic(() => IsServerBuild)

.DependsOn(Compile)

.Executes(() => { });

By using the Requires construct, Nuke will throw an error if that target is being invoked without using the -ApiKey or -api-key parameter and no similarly named environment variable exists. However, this target will only try to do this if you’re running the build from a build server such as AppVeyor, TeamCity or any of the other supported environments.

Dynamic command-line help

For example, running build.ps1 --help on one of our projects gives you this.

NUKE Execution Engine version 0.24.0-alpha0215 (Windows,.NETCoreApp,Version=v3.0)

Targets (with their direct dependencies):

Clean

ReportVersion

Restore

StartSqlServer

SonarQubeBegin

DotNetBuild -> Restore, SonarQubeBegin

EnsureNpmRcInitialized

JsBuild -> EnsureNpmRcInitialized

UnitTests -> StartSqlServer, DotNetBuild

SonarQubeEnd

StopAndRemoveSqlServer

Publish -> UnitTests, JsBuild

Pack -> Publish

Push (default) -> ReportVersion, Clean, Pack

Parameters:

--artifactory_password <no description>

--artifactory_username <no description>

--configuration Configuration to build - Default is 'Debug' (local) or

'Release' (server).

--git_access_token The auth token to connect to the private Github repository.

--github_path The FQDN of the Github repository.

--myget_auth_key <no description>

--sonar_host_url The FQDN of the SonarQube server to connect to.

--sonar_login The user name to connect to SonarQube.

--project_id The Build Configuration ID of the project in Team City.

--to_main_feed If set to a non-empty value, packages will be pushed to the

main Artifactory or Myget feed.

--continue Indicates to continue a previously failed build attempt.

--help Shows the help text for this build assembly.

--host Host for execution. Default is 'automatic'.

--target List of targets to be executed. Default is 'Push'.

--no-logo Disables displaying the NUKE logo.

--plan Shows the execution plan (HTML).

--root Root directory during build execution.

--skip List of targets to be skipped. Empty list skips all

dependencies.

--verbosity Logging verbosity during build execution. Default is

'Normal'.

Notice the parameter documentation that Nuke extracts from the parameter declaration?

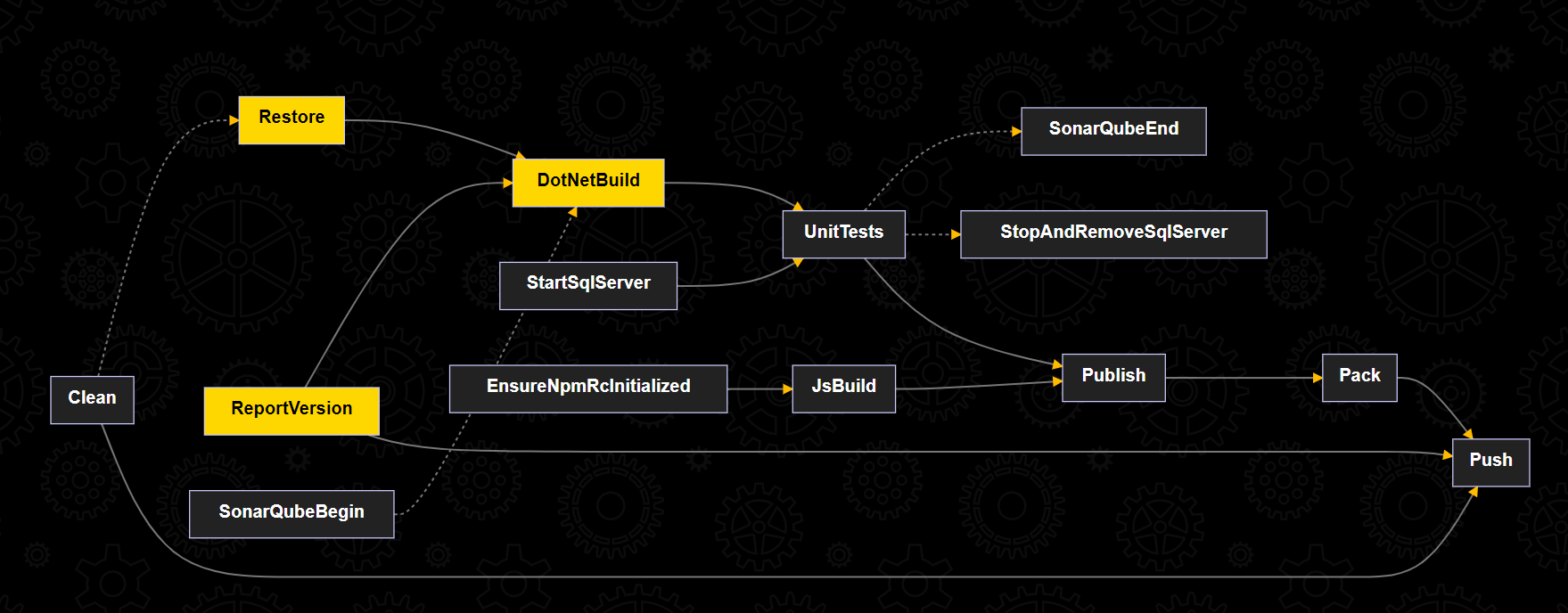

Can display a dependency graph

Running build.ps1 --plan on that same project I used for demonstrating the command-line help, this is what it will display in your default browser.

And what’s cool is that hovering on any target will visualize its dependencies by high-lighting them in yellow. This is particularly nice to understand the parallelizable paths in bigger build scripts.

Prepared for parallel execution

If you use a build automation tool like Nuke in a more serious project, and you haven’t fully bought into the microservices hype, it’s very likely that your build grows considerably over time. This usually also comes with an increasing execution time that can become quite annoying if the code churn is very high. One of the first things developers look at is trying to speed up the individual steps, e.g. by updating build tools like Webpack, or by disabling certain steps on local development machines. After that, they will look for opportunities to identify multiple independent paths that they can run in parallel on build servers that support chaining builds.

A unique aspect of Nuke is that their target dependency model is prepared for parallel execution, something which no other build framework can support without introducing serious breaking changes. Let’s look at the previous example again.

Target Pack => _ => _

.DependsOn(ApiChecks)

.DependsOn(TestFrameworks)

.DependsOn(UnitTests)

.Executes(() =>

{

//

});

This will tell Nuke that the Pack target needs the three targets ApiChecks, TestFrameworks and UnitTests to have run before itself should run. But unlike Cake or PSake, this does not imply any specific order. You can define some ordering using the Before, After and Triggeres constructs, but that’s not recommended. The Nuke team is working on fully parallelizing execution of targets without you having to think too much about that.

Built-in logging abstraction

You don’t need a 3rd-party package just for logging. Nuke has everything build in and even understands how to enrich the logging for your specific build server. For example, if you’re running on TeamCity, Nuke will automatically emit service messages that TeamCIty will use to allow you to collapse the log file into target-specific blocks.

From inside your build script, you can use things like (bluntly copied from the docs)

Trace($"Example {Solution}");

Normal("Example {0}", Solution);

Info(Solution);

Warn("Warning!");

Error("Error!");

Error(exception);

Success("Finished.");

If you’re running on a console window, it’ll use colors to emphasize warnings and errors and give you nice readable blocks like this:

Easy to support any external tool

Like Cake, Nuke comes with a lot of built-in fluent APIs for common tools like MSBuild, GitVersion and Xunit, and the community is growing by the day. The advantage of this is not only that you don’t have to build complicated argument strings from C#, it also properly handles exceptions and automatically provides the right level of logging. But there’s always a parameter or tool that a build automation framework like this does not support. This is where Nuke’s CLI support shines.

For instance, if you want to customize the arguments passed to an already supported tool, just use the SetArgumentConfigurator method like in the following example:

MSBuild(o => o

.SetTargetPath(SolutionFile)

.SetArgumentConfigurator(a => a.Add("/r")));

Using your own tool is quite trivial as well. Just define a property of type Tool which name matches the executable to use (or provide the name as an attribute argument).

[PathExecutable("dotnet-sonarscanner")]

readonly Tool SonarScanner;

SonarScanner("end /d:sonar.login=dennisdoomen");

In this case, Nuke will assume that the executable will be available in the current path (e.g. %PATH% on Windows). But if your executable is part of your source control repository, you can also use this format.

[LocalExecutable("./tools/dotnet-sonarscanner.exe")]

readonly Tool SonarScanner;

Nuke even supports invoking tools that it downloads through a NuGet package:

[PackageExecutable(

packageId: "xunit.runner.console",

packageExecutable: "xunit.console.exe")]

readonly Tool Xunit;

Supports running an action on multiple files with ease

It’s not that big of a feature, but Nuke also supports using a declarative way for ensuring that a particular tool is run on a collection of values. The syntax is quite flexible, but this is an example of what it can look like.

var publishCombinations =

from project in new[] { FirstProject, SecondProject }

from framework in project.GetMSBuildProject().GetTargetFrameworks()

from runtime in new[] { "win10-x86", "osx-x64", "linux-x64" }

select new { project, framework, runtime };

DotNetPublish(o => o

.EnableNoRestore()

.SetConfiguration(Configuration)

.CombineWith(publishCombinations, (oo, v) => oo

.SetProject(v.project)

.SetFramework(v.framework)

.SetRuntime(v.runtime)));

Paths are a first-class citizen

Another little but very neat feature is its first-class support for building paths from variables. Consider the example below.

AbsolutePath TestsDirectory => RootDirectory / "Tests";

AbsolutePath TestFrameworkDirectory => TestsDirectory / "TestFrameworks";

NSpec3(TestFrameworkDirectory / "NSpec3.Net47.Specs" / "bin" / "Debug" / "net47" / "NSpec3.Specs.dll");

What Nuke does is override the / operator on an AbsolutePath type so that you can build up a complicated path definition without bothering with the dreaded Path.Combine or StringBuilder class. It really removes a lot of noise from your build scripts.

Is it all sunshine and rainbows?

Well, the dependency model is very different from other comparable build tools, so converting existing build scripts can be quite a challenge. But after you do, like me, you’ll never look back. I can’t think of a single thing that Cake, BullsEye or PSake does better. But don’t believe me on my blue eyes. Try it yourself or check out the build script of my pet project Fluent Assertions.

So what do you think? What is your experience with build automation tools? Let me know by commenting below. Oh, and follow me at @ddoomen to get regular updates on my everlasting quest for suggestions and ideas to become a better professional.

Aviva Solutions

Aviva Solutions

Fluent Assertions

Fluent Assertions

Leave a Comment